9 Unit :9 :Developing Policy for Learning Analytics

Having now studied several units of this course, you’ll be more aware of the extent to which institutions collect, analyse and use student data. For many institutions, formal guidance or policy on how and why this is done may not yet exist, particularly if uses of learning analytics are relatively new or have not yet begun. For others, existing policies relating and referring to potential uses of student data may need fresh scrutiny to ensure their continued relevance and completeness. This unit sets out some of the steps involved in creating a policy framework, advises on key principles and provides examples of existing educational policy that might provide a useful starting point. Having studied the unit, you should be able to prepare a preliminary outline of the steps involved and what a policy might look like in your own context.

Learning outcomes

After you have worked through this unit, you should be able to:

- explain the key features and purpose of a learning analytics policy

- compare and contrast learning analytics policies at the national and institutional levels

- use the template provided to draft the outline of a context-specific learning analytics policy

It’s fair to say that many educational institutions have a whole pile of formal policies tucked away on their website (or perhaps not even open for scrutiny) that very few ever read. Yet the purpose of having a visible policy is multifaceted.

Fundamentally, a policy should make clear to all stakeholders what the institution’s position is on the issues. It should explain the background and the need, establish any boundaries (what is included and what is not) and justify assumptions. Any new policy should support and not conflict with other existing policies (or require that those be revised to remove that conflict). Unlike guidance or a framework, it will do more than suggest, but seeks to clarify acceptable practice and make formal the “rules” around a particular issue.

Learning analytics is a relatively new practice for many educational institutions. Student data have been collected for many years, often for reporting or operational purposes, but the range of data now collected for learning analytics, and the reasons for its collection, warrant a fresh look at whether additional policy is required.

A hidden benefit of policy creation is that it forces key stakeholders to fully consider the range of issues — the context; the boundaries; the purpose of the process/activity; who it is important to; who needs to be involved in the decision making; and what needs to be covered. Policy creation is no easy exercise; it requires rigour, research and resilience!

The steps needed to create a new policy will depend, in part, on the size and complexity of the organisation, current and planned future uses of learner data, existing policies, and relevant (inter)national or federal law. The following steps may not always apply, but it is recommended that they be at least considered in order to produce a robust outcome relevant to your own context. Ideally, policy should be set out and agreed before the introduction of learning analytics in your institution, as it should guide the application of learning analytics in your contexts. Realistically, as more institutions adopt some form of learning analytics, policy creation is likely to be a retrospective process. In such cases, extra care should be taken to ensure that ongoing learning analytics are driven by the final policy rather than the other way around.

1. Form your team

Start with a small team (preferably five or fewer). Ensure that you have a project lead and a project manager. You will also need members who understand some or all of the following: current or planned uses of learning analytics; data protection issues; how policy is created within your organisation. Be prepared to meet regularly — e.g., monthly — and be clear about what is expected from each member. Keep a well- defined record of all discussions and agreed objectives. Maintain a shared space for collecting and sharing relevant resources. Agree on a schedule and a meeting frequency.

2. Agree on and set the purpose

This is perhaps the most obvious and yet potentially the most overlooked stage of creating any policy. Before the organisation begins to draft any new policy, it must first understand what it is trying to achieve.

In the case of implementing a learning analytics policy, the purpose might be very specific — for example, to improve learner completion or pass rates at a course level. Or perhaps a more general aim would be to better understand how learning design has impacts on learner success. Once discussions have begun, it will become clear that boundaries need to be set. For example, are there any activities or groups of stakeholders that must be included or would be excluded from the policy? In the case of learning analytics, you may wish to consider whether teacher data are included, for example, or whether all data collected by the institution will always be used. An example of the latter might be the following statement:

All data captured as a result of the institution’s interaction with the learner has the potential to provide evidence for learning analytics. Data will only be used for learning analytics where there is likely to be an expected benefit to learners’ study outcomes.

It is perhaps better to develop a purpose that covers current (or planned) learning analytics activities than to try to cover all future eventualities. Learning analytics is a fast-moving field. Start simple. If your organisation focuses on, for example, providing interventions for learners not meeting certain deadlines or tasks, it will be simpler to define your aims and scope than if you assume that it will at some point move into machine learning.

3. Research

It is essential to understand the organisational context in which the policy will exist. Time should be spent investigating existing policy, and understanding how uses of learning analytics are likely to have an impact on your organisation’s aims and the needs of key stakeholders going forward. Key related policies here (depending on your particular institution) are most likely to be related to data protection and data retention.

You may consider whether the uses of a range of technologies also comes into play here — what technologies (e.g., apps used on mobile devices, personal computers, websites, etc.) are used to deliver learning in your setting. How are learner data captured and shared, and with whom?

At this point, it would be useful to review existing policies and best practice for uses of learning analytics in other comparable learning institutions. Fundamentally, some of your consideration should be directed to understanding how existing and planned legislation may constrain your planned approach, as well as specific data sets that may be out of bounds for certain analytics activities (as discussed in Unit 7). In many countries, you will certainly need to understand what is meant by “personal information” and/or “sensitive information,” as these categories are often more constrained in terms of what can be collected and used within learning analytics. An example of personal information that may not be collected in some US states is a student’s social security number. In the European Union, personal information includes any information that relates to an identified person or one who could be identified, directly or indirectly, based on the information. Whether it may then be used for learning analytics purposes could then depend on whether it is further classified as Special Category Data (e.g., religious or philosophical beliefs).

Here are examples of data protection legislation in a range of geographic contexts:

- The Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA) governs how private-sector organisations collect, use and disclose personal information. However, for public sector bodies, such as schools, provincial and territorial privacy laws apply.[38]

- The Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act of 1974 (FERPA[39]) addresses the privacy of student education records in the United States. Note that state law can also apply in the US — for example, the California Consumer Privacy Act 2018 (CCPA[40]).

- The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR[41]) in the European Union.

- In Australia, the Privacy Act (1988) [42] regulates how government agencies (amongst others) handle personal information, although again, other state and territorial legislation may also apply.

- You should also consider whether any aspects of organisational practice cross (or are likely to cross) national or state legislative boundaries. For example, are there any activities that involve data transfer outside of your country? How might this affect your policy statement?

4. Identify key elements and draft the structure

Based on your understanding of the purposes of using learning analytics and of the relevant policies and legislation, you should now be able to establish an outline for your new policy. A suggested outline might contain sections such as:

- Introduction/background

- Definitions (of terms used, etc.)

- Scope/boundaries – what learning analytics activities and data types are included in the policy, and which are out of scope; who can access student data and any resulting analytics within the institution

[39] FERPA: https://studentprivacy.ed.gov/node/548/

[40] CCPA: https://oag.ca.gov/privacy/ccpa

[41] GDPR: https://gdprinfo.eu/

[42] The Privacy Act: https://www.oaic.gov.au/privacy/the-privacy-act/

- Relevant institutional policy and legislation

- The principles underlying the policy

- Implementation strategy and timeline

- Review process and policy owner(s)

5. Stakeholder input and ongoing review

Much of the time taken to develop a meaningful policy is invested at this stage. If your new policy is to get genuine buy-in, you need to engage with all representative and relevant stakeholders. Consider: who does learning analytics impact, and who is driving the agenda to adopt learning analytics within your organisation? This is really an iterative process, but you should first meet with different stakeholders to capture their views on issues such as acceptable uses of learning analytics and data types, and then revisit those groups once you have developed sufficient content. This is not an all-inclusive list, and remember, you have considered relevant stakeholders for learning analytics in Unit 8, but your stakeholders might typically include:

- Learners. Is there a recognised panel or body in place? If not, you might consider a consultative forum or survey to gather input. Don’t be tempted to skip this group; they are perhaps the most important of all stakeholders. Be aware that raising the issues around uses of learning analytics may create unease for some, so be prepared and be clear on the purposes, boundaries and data categories.

- Course leaders/course teams. How might they use learning analytics?

- Information technology staff. Data storage issues, etc.

- Management. Depending on the size and structure of your organisation, this might be more or less difficult. Either way, new policy creation will need formal approvals from the relevant governing body, and it is sensible to seek input from relevant members of your leadership team to avoid unpicking work at a later stage.

- Key administrative representatives, such as those engaged with registration, enrolment, student support, etc.

- Teachers. As potentially important end users, they will have useful input on how learning analytics might best inform their practice, and they can flag any immediate shortcomings and/or missing issues.

- Researchers. Researchers may feel that their uses of data are covered by other existing policies. It is worth checking, though, and ensuring that all stakeholders are clear on the differences between seeking approvals for data for research purposes and accessing data for operational purposes.

6. Develop the content

It may be tempting to create a report of the process you’ve gone through, but be mindful that a policy should contain content that is relevant and digestible. Keep it succinct where possible, and set broad aims and objectives. Unless unavoidable, try not to identify specific technologies, as these are likely to evolve as your analytics capability develops. On the other hand, those issues used to define the scope of activities should be retained and made clear. It is perfectly acceptable to refer to other documents that may contain more detail, so long as these are also accessible to pertinent readers.

7. Gain approval

Revisit your key stakeholders and check that your proposals meet with approval. You may find that something emerges at this stage that causes you to revisit an aspect or an assumption; most policy development is an iterative process. At some point, you will need to be prepared to move forward without satisfying every individual. Having said that, your policy must have agreement from your leadership team, and if you are unable to satisfy everyone, be clear why you can’t. For instance, you may find that you have conflicting interests between stakeholders; you must be prepared to take a stance and agree on a way forward that meets the agreed purposes and scope, and also satisfies formal or legislative requirements.

Make sure that your written policy is set up in line with your organisational requirements and, if needed, get an understanding of the formal process for approvals.

8. Regular reviews

Policy documents are not static. As might be expected in a fast- moving field, learning analytics will continue to evolve, and activities and approaches that may have been considered unlikely or out of scope may need to be considered in the future. New legislation may provoke the need for review (such as the introduction of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in the European Union). As with all organisational policies, aim to ensure that your shiny new learning analytics policy is reviewed and updated regularly.

9. Implementation

Development of your policy will no doubt have thrown up a number of issues, and you should consider how these are resolved. If, for example, you have committed to the users of learning analytics being able to understand and interpret learning analytics, you may need to implement some kind of data interpretation training. Creating your policy will be an achievement, but remember, it is of little use if all of those affected by uses of learning analytics in your institution are unaware of it. Promote it in ways that maximise the likelihood of engagement with it. This may mean creating user-friendly versions with links to fuller, more formal versions, creating video content for websites, running workshops, etc. Be creative! The word “policy” is unlikely to generate much excitement, so think of ways that you can entice stakeholders to read and understand your carefully crafted words.

The first formal policy for educational uses of learning analytics was created in 2014 at The Open University (OU) in the UK, and it is well established as a model on which many subsequent institutional policies have been developed. The process of creating the policy took just under two years, drawing upon published research, legislation and significant input from several stakeholder groups. The OU’s policy is built around eight key principles that reflect its open, distance learning ethos:

- Learning analytics is an ethical practice that should align with core organisational principles, such as open entry to undergraduate- level study.

- The OU has a responsibility to all stakeholders to use and extract meaning from student data for the benefit of students where feasible.

- Students should not be wholly defined by their visible data or our interpretation of that data.

- The purpose and the boundaries regarding the use of learning analytics should be well defined and visible.

- The university is transparent regarding data collection and will provide students with the opportunity to update their own data and consent agreements at regular intervals.

- Students should be engaged as active agents in the implementation of learning analytics (e.g., informed consent, personalised learning paths, interventions).

- Modelling and interventions based on analysis of data should be sound and free from bias.

- Adoption of learning analytics within the OU requires broad acceptance of the values and benefits (organisational culture) and the development of appropriate skills across the organisation.

An overview of the OU’s policy is available at:

Other useful frameworks include the UK JISC’s Code of Practice (2015) [44]; the EU-funded DELICATE checklist, produced by the Learning Analytics Community Exchange (LACE, 2016); [45] and the University of Wollogong’s policy (2018). [46] As mentioned in Unit 8, the SHEILA framework [47] includes very helpful guidance for reviewing your institution’s capacity to adopt learning analytics, and we recommend that you review each of dimensions included to ensure you have considered the most important factors.

[43] A full copy of the policy with greater detail of, for example, included and excluded data sets can be found at: https://help.open.ac.uk/documents/policies/ethical-use-of-student- data/files/22/ethical-use-of-student-data-policy.pdf

[44] https://www.jisc.ac.uk/guides/code-of-practice-for-learning-analytics

[45] http://www.laceproject.eu/ethics-privacy/

[46] https://documents.uow.edu.au/about/policy/alphalisting/uow242448.html

[47] https://sheilaproject.eu/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/SHEILA-framework_Version-2.pdf

Activity: Complete a template for drafting your own policy

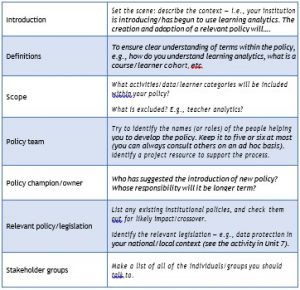

Now that you’ve had an overview of the steps involved in policy creation, you may be feeling a little daunted by the task ahead. Don’t be! Copy and paste the template below into a fresh document. Don’t spend too long at this stage. Fill in as many parts of the table as you’re able; this may help identify which areas you’re already well prepared for, and where further thought or effort is required.

This should be enough to get you started. Don’t attempt to set out your guiding principles by yourself — they will flow from your discussions with stakeholders and your research.

There are a number of guides to producing policy, depending on the complexity of your needs and the time you have available. You may find this UK Government resource, “Policy Lab in a Day,” [48] helpful to get you started if you’re planning to develop policy within a team.

[48]

https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5791f90de5274a0da30001a1/Policy_Lab_in_a_day.pdf

This unit has tackled an often forgotten aspect of learning analytics: creating and maintaining a policy (or at the very least, a set of principles) to guide how your institution will engage with learning analytics. Although the language of policy can be very dry, creating a policy will really open your eyes to what you want to use analytics for and where you should tread carefully. Good luck!

a. What is the point of creating an institutional policy for learning analytics (choose all that apply):

i. It sets out in a formal, transparent way how and why the institution will collect, analyse and use learner data.

ii. It’s a hoop that the institution has to jump through.

iii. It allows the institution to use student data in whatever way it wants.

iv. It drives the future uses of learning analytics within the organisation.

v. It creates a shared understanding for all stakeholders and helps to get each group on board.

b. Is it possible to apply existing policy from another institution? (choose one)

i. Yes, the issues are fundamentally the same.

ii. Yes, with consideration of institution-specific issues.

iii. Yes, with consideration of institution-specific issues and relevant legislation.

iv. No, every institution is different, and it would be more efficient to start from scratch.

c. What is the most important issue when creating a new policy concerning uses of learning analytics?

i. what you want to achieve

ii. the data available to you

iii. the package your institution has already purchased

iv. existing relevant legislation

v. stakeholder views

d. What is the first thing you should do when creating a policy for learning analytics?

i. come up with a name for the policy

ii. find an existing learning analytics policy to check out

iii. define the purposes of learning analytics at your institution

iv. identify the data sets available

v. talk to the learning analytics champion and find out what they want most

e. What are the benefits of consulting stakeholder groups? (choose all that apply)

i. getting a broad range of input from different perspectives

ii. proving that you have asked people who might object to what you are planning

iii. getting buy-in from those who might be impacted by uses of learning analytics

iv. highlighting issues that you may not have thought of

f. Who are the most important stakeholders?

i. the senior management team

ii. learning analytics developers/researchers

iii. IT staff

iv. learners

v. teachers

g. Do users of learning analytics in your institution have to take any notice?

i. Yes, the policy sets out the rules.

ii. Yes, if the policy supports what they plan to do.

iii. Not if they are not aware of it.

iv. No, it is guidance only.

h. Which of the following informs what goes into your policy? (Choose all that apply.)

i. the software you plan to use/are using

ii. the learning analytics activities you plan to carry out

iii. the data available to be collected

iv. relevant institutional policy and external legislation

v. examples of existing learning analytics policies

vi. stakeholder views

i. What must be done to make sure your new policy takes effect?

i. Tell the policy owner it is complete.

ii. Publish it on your institution’s website.

iii. Get formal approvals (if applicable).

iv. Email the stakeholders and send them a copy.

j. When should you update your policy? (choose all that apply)

i. every year

ii. when senior managers tell me to

iii. according to the agreed review process

iv. when relevant legislation changes

v. Never

k. You’ve written your policy. What next? (choose all that apply)

i. Take a well-earned rest.

ii. Consider any implications.

iii. Forget it and move on.

iv. Publicise.

v. Review and update regularly.